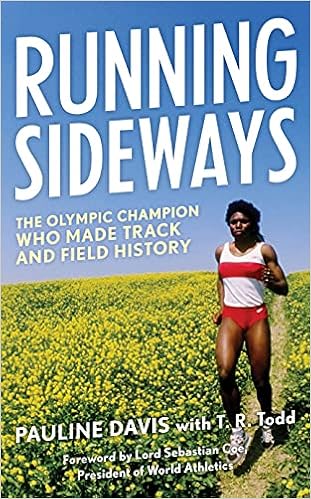

Pauline Davis-Thompson (© Christel Saneh)

For many young people from underprivileged backgrounds, athletics is a way out of poverty.

On the tiny island of The Bahamas, at a time when the country was yet to find Olympic success, Pauline Davis – a young woman born and raised in the poor neighbourhood of Bain Town – would emerge as the Golden Girl of The Bahamas, and pave the way for young women from her country to follow in her footsteps.

In a new book titled ‘Running Sideways’, Davis-Thompson shares her journey of how she fought through poverty, inequality and racism to beat the odds and become a two-time Olympic gold medallist.

A raw, uplifting story from one of the most important hidden figures in track and field history.

A raw, uplifting story from one of the most important hidden figures in track and field history.

Running Sideways is a book about determination, faith, focus, and an incredible will to succeed. It’s about a trailblazer in women’s sports, not just in The Bahamas, not just in track and field, but on the global stage.

Childhood in Bain Town

Growing up on Fleming Street in Bain Town, a poor neighbourhood of The Bahamas, Davis-Thompson took pride in being raised by the entire village. Discipline and education were top priorities for her mother Merle Davis Toussaint, who is originally from Jamaica. They are two values which also served Davis-Thompson well in her career as an athlete.

“My mummy used to say, ‘When you are poor, there are lots of things to know.’ In other words, you find ways to get by with what you have,” Davis-Thompson writes in her book.

She spent her childhood playing outside with the kids of the town. Davis-Thompson’s gift was speed, and that was obvious to everyone, including the children she played with, but not to herself. When hanging out with other children in her village, the relay was one of the many games they played. The purpose of it was to run, climb a coconut tree, get the fruit, and give it back to the other teammate who would go on and repeat the process.

My friends used to say to me: “How you get up there so quickly?”

Davis-Thompson was very competitive, and would play different sports growing up. She even cut her hair to play football with the boys, because back then young girls weren’t allowed on the team as it was considered unfeminine.

Challenging people’s assumptions would be something she would live by and would push her to achieve her ultimate best in sporting competitions.

The eldest of six siblings, Davis-Thompson’s tasks at home were more physical. With no running water in the house, when the water buckets were empty, she would be the one running towards the Government Tap to fill them up. But along the way she would often face bullies who would chase her down the street.

“No way they catch me. But this ain’t a simple foot race. I wasn’t coming home with empty buckets—I’d be liable to get the switch. I didn’t want to spill a single drop.

“Ever sprint, as fast as you can, with two open buckets of water? It ain’t easy.

“Of course, in such a situation, you don’t think too hard about technique. You don’t think at all. You do whatever you have to do to get the job done. As I ran from those boys – down Fleming Street, in the heart of the ghetto – I was twisting my body to the side. It just came naturally to me. How else would I protect the water?

“There I was, hands close to my chin, my body cocked to the side. I was running sideways.” Davis-Thompson remembers in her book.

“When I run, I often close my eyes. I close them so I can focus on the feeling of running, or I might lose it—that rhythmic pounding of my feet. As I get close to top speed, it feels like I’m floating. My legs come out from underneath me. So I have to close my eyes and concentrate, to make sure I don’t float. That’s how I stay grounded. I zone everything else out in the world, everything that is around me, so I don’t lose my place in time.

"That little girl had no clue what was in store for her. She had no idea that, one day, Bain Town would be replaced by the bright lights of a stadium, packed with thousands of people, screaming and dissecting your every stride. That millions of others would be watching her on their television sets, or listening to the radio, from all corners of the world. Those dusty streets of Fleming Street would eventually become a rubber track. Those buckets, a baton. Nobody is chasing her—she would run down the most elite sprinters on Earth."

Much would change for the girl who ran sideways as she always had something to prove.

Polishing a raw pearl

While it was obvious to everyone in town and in her school that Davis-Thompson had a gift, she was still far from realising that running could change her life.

Frank Rutherford, who became the first Bahamian athlete to win an Olympic medal for the country, was the first to convince her to join the school team. He was determined to deliver his coach’s message to her, and he finally succeeded.

Coach Neville Wisdom would go on to convince Davis-Thompson’s father to allow Davis-Thompson to join the team. In turn, Davis-Thompson’s father achieved the more difficult task of convincing her mother that running would be a way out.

Davis-Thompson’s mother, who would later graduate as a nurse, agreed on one condition: that Davis-Thompson would have to excel in school. Davis-Thompson kept her promise to the woman she describes as her No.1 role model.

It wasn’t easy for Wisdom to polish this little girl he called ‘Pearl’. He played a vital role in her career, supporting her from day one and fixing her running technique – namely her habit of running sideways. He also became what she describes as ‘coach dad’. He welcomed her in his family and as a daughter; he never lost sight of her, even after she left The Bahamas to attend college in the US.

International Women’s Day Special: ‘Running Sideways’ | Pauline Davis-Thompson in conversation with Seb Coe

Download the full podcast for free via iTunes or Spotify.

All past episodes, including links to the podcast on a range of streaming platforms, can be found on Audioboom.

First taste of glory

The girl from Fleming Street, who ran barefoot to get water and escape the bullies, living in a house with no plumbing or electricity, didn’t know back then that her struggles would provide a source of motivation and power to prove herself over and over in her bright career as an athlete.

“When people look at decorated athletes, all they see is glory,” she writes. “They only see the finish line. But my path would often be a solitary one, and full of sacrifice, and discipline – traveling on my own from city to city, from country to country, all the while representing my tiny country, by myself, to the world. The ability to be myself, and be happy about it, was so crucial.”

Following in Merlene Ottey’s footsteps as an emerging young talented woman in athletics from the Caribbean, Davis-Thompson was selected to compete at the 1982 Carifta Games in her home country, her first major championships. But, aged 14 at the time, Davis-Thompson missed the competition due to a severe flu, an illness that would resurface during her career as a professional athlete.

She had to wait another year for the next Carifta Games, held in Jamaica. The Bahamian team was hosted in a school, girls sleeping in one room, the boys in another. The coaches didn’t have proper beds to sleep on; they simply slept on the ground. Transportation was unique, too. An army truck would shuttle the team to the track. One day, the first truck set on fire, forcing the athletes to jump off and wait for a second truck.

“For us, in the back of that army truck in Kingston, Jamaica in 1982, it just shows how much track and field meant to us, and to The Bahamas,” she writes. “It was like going to war.”

This, however, was just the start of her incredible journey on the track.

At the 1983 Carifta Games, Davis-Thompson wound up winning silver medals in the 100m and 200m. Overall, however, Jamaica earned most of the medals and finished comfortably ahead of The Bahamas on the medals table. Aware of the rivalry between the two Caribbean countries, Davis-Thompson would not accept another defeat.

Her competitive spirit lifted the entire team’s spirits to finally succeed in the Central American and Caribbean (CAC) Junior Championships the same year. She had one thing in mind: run her competition into the ground. And so she did. She took home the gold in the 100m, 200m, 400m and even the long jump. The Bahamian team returned home victorious with 14 gold medals.

The same spirit would reign on the next Carifta Games. Davis-Thompson won gold in the 200m, took silver the 100m, and the team collected 14 golds to finish ahead of Jamaica in the medal standings. Since then, Davis-Thompson never missed a chance to be at the Carifta Games, during and after her career.

Travelling the world to run

Davis always looked up to Wilma Rudolph, an athlete who overcame Polio to win the 100m, 200m and 4x100m at the 1960 Rome Olympic Games. Rudolph served as a constant inspiration during struggles or in moments of doubt.

“If Wilma Rudolph can overcome all of that, what’s stopping me,” Davis-Thompson would think.

Her first global event was the inaugural World Championships in Helsinki in 1983, where Davis-Thompson met athletes she admired and soon enough became her friends – the likes of Evelyn Ashford and Carl Lewis.

The following year, she qualified for her first Olympics, despite suffering a hamstring strain, while also working in McDonalds and as a hotel receptionist to pay for college. She qualified for the 1984 Olympic Games in Los Angeles at the age of 16. She reached the semi-finals in both the 100m and 200m, and finished sixth place in the 4x100m with Eldece Clarke, Debbie Green, and Oralee Fowler.

At that point, the stress of athletics, work and education got the better of her. It was time for her to enter college and she hadn’t yet received any offers, while athletes of the same calibre had numerous offers.

“One day in the village, on my way back to the cafeteria, I remember fainting and crashing to the ground,” she writes. “Fortunately, a couple teammates were there to help. They carried me to the athlete facility, where doctors monitored me for a few hours.

“In the end, there was nothing seriously wrong with me. I wasn’t sick or injured. High school. College entrance exams. My two part-time jobs. Training. The Olympics. And of course, wondering and worrying about whatever comes next. I think all of these things weighed on me. And I crashed.”

Two weeks before she started college, coach Wayne Williams called coach Wisdom’s house where Davis-Thompson was staying. She answered the phone to learn that the University of Alabama wanted to recruit her. She agreed right away.

She had no idea what racism was until she went to the university in the US. Previously at World Championships, she realised people looked differently, had different skin colours, but until then, she had never faced issues in The Bahamas. Her godfather, who was white, treated her family the same way as anyone else. During her college years, she faced many issues because of the colour of her skin. The one thing that kept her going: she was there to run.

Excellence despite it all

Davis-Thompson never stepped back when faced with challenges. She fought through poverty, illness, inequality and racism. When the political system in her country wanted to drag her down, she rose and made her country proud, eventually rising as a champion.

“I always understood this: you really had to be even more of an achiever to get noticed and cross over that invisible line,” she writes.

At her fifth Olympic Games in Sydney in 2000, Davis-Thompson initially finished second in the 200m behind USA’s Marion Jones, who was later stripped of her medals after she admitted to taking performance-enhancing drugs. Davis-Thompson waited nine years to finally receive her gold medal. She became an advocate for clean sports.

When she received her medal, she offered it to the Prime Minister at the time, saying: “This medal is for the people of The Bahamas.”

Her only regret was not getting to hear her national anthem on the podium for the 200m. After earning silver in Atlanta four years earlier in the 4x100m, she went on to win the 4x100m with her teammates. The Golden Girls, as they were famously called, were welcomed as heroes in The Bahamas.

“My race was never a straight line, but I got to where I wanted to go. It proves that it doesn’t matter how you start off in life – it’s how you finish.”

In 2007, Davis-Thompson became a member of the World Athletics council.

Her message to young women

“I want young women to understand that life is not going to be perfect. They are going to meet speed bumps, they’re going to meet hurdles. But it's how they navigate them that will determine what they're able to achieve in life,” she tells World Athletics President Sebastian Coe in an International Women’s Day podcast special.

“Number one top priority is education. They’ve got to make sure that they get their education because once you have your education, no one can cut you open and remove it. You have to have a sense of purpose; you have to know why you want to do what you're doing.

“But just understand that nothing in life is ever perfect. But you have got to navigate it. When they knock you down, you'll get up, you brush yourself off and you keep on pushing. You never ever, ever, ever quit, ever.”

Christel Saneh for World Athletics